The Weapons

Kobudō is the study of the weapons of ancient Okinawa. These are not the sword and spear of the samurai of Japan. Most of the weapons of ancient Okinawa were farming and fishing implements. The use of some of the implements as weapons may long predate the invasion of Okinawa by the Satsuma of Japan in 1609. The possible origin of each weapon is discussed, though sometimes the exact origin has been lost in time.

Why Study the Weapons of Ancient Okinawa?

The weapons of ancient Okinawa are not something you will see carried in the streets of modern America. You may not even be able to find a particular weapon except for purchase from a specialized martial arts supply store. in some states carrying around certain of the weapons of kobudō can get you into trouble with the law. At least in karate you always have your weapons, your hands and feet. So is karate is more practical than kobudō? True, the martial artist does not carry his weapons but in a pinch anything can become a weapon: a rock, a cane, an umbrella, a walking stick, a pen. A martial artist should think how he could use the objects around him as a weapon, and how he would defend himself if the objects were used against him.

Describing the Weapons

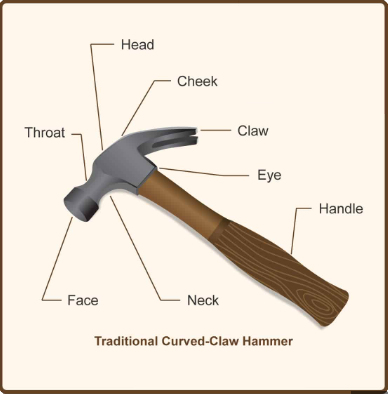

An attempt has been made to name the parts of each weapon in Japanese. You may find that there are other names. That is not surprising. Like the grip, the shaft or the handle of a hammer, there can be several words to describe each part. It is likely that only a wood craftsman would know all the names of the parts of a hammer.

You, too, are a craftsman, a craftsman of kobudō. Knowing the names of the parts of a weapon can be a shortcut to accurate communication when discussing weapons techniques. For example, if the sensei says kontei zuki, it is useful to know that you are to thrust with the base of the nunchaku rather than the string end.

The Weapons of Kōburyū Kobudō

Roku Shaku Bō

六尺棒

The bō (or staff) comes in many lengths. Koburyū kobudō includes just the six foot staff, roku shaku bō. It is the kobudō student’s first weapon. The bō is used to strike, thrust, parry, sweep and smash.

Origin

The bō was used as a walking stick or could be used to balance pails of water across a peasant’s shoulders. Because it was a common sight, bō could be carried openly even during times when weapons were banned. The warrior class of ancient Okinawa used bō for sword and spear training. You can still see this influence in the movements of bō kata.

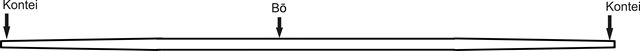

| Bō | 棒 | pole; rod; stick |

| Kontei | 棍底 | bottom or base of a stick |

| Monouchi | 物打ち | the striking area |

The Parts of a Bō

When performing an uchi (a srike with the side bō) the striking area on the bō is called the monouchi. It is not at the very end of the bō, but an area a few inches in. Every striking weapon has a monouchi, the area of most effectiveness for striking.

Sai

釵

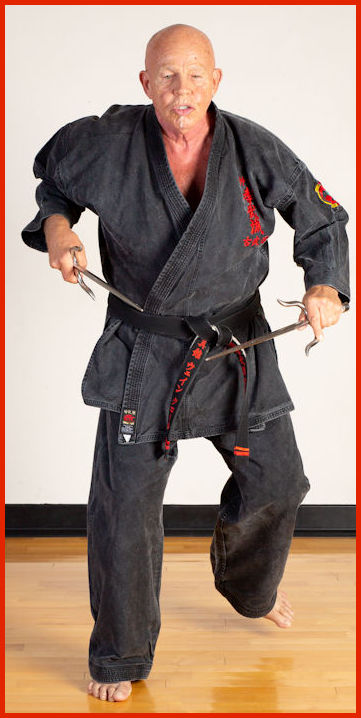

Sai is the kobudō student’s second weapon. Sai are used in pairs. They can be gripped with the long end of the sai against the forearm to punch and block. With the grip flipped, the sai can be used to stab, parry, sweep and smash.

Origin

The sai was never a fishing or farming implement. It was certainly never used to create furrows or poke holes for planting seeds. Sai were carried in pairs and were a symbol of police authority. Not just a deterrent, sai could be used to effectively defend against a sword, deflecting a cut and forcing the sword aside so the defender could thrust with the second sai. Reversing the grip, the blunt end of the sai could be used to add power to a punch.

Metal is not found on the island of Okinawa. It was first introduced to Okinawa in the 1700s. Since metal was very scarce and had to be imported the sai, made of metal, made an impressive show of authority.

The kanji for sai is the same as the kanji for an ornamental hairpin. Does this mean that sai were once worn in the hair? Not at all, but sai are shaped similar to the hairpins once worn in a Japanese woman’s hair.

Sai may actually have been designed after the Japanese weapon, jutte (or jitte). In feudal Japan, it was a crime punishable by death to bring a sword into the shogun’s palace. The jutte was a non-bladed weapon, some versions of which looked remarkably similar to a sai. Carried by palace guards, it proved to be especially effective and became the palace guard’s symbol of authority.

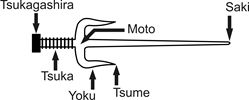

The Parts of a Sai

| moto | 基 | base |

| saki kissaki | 先 切っ先 | tip point of a sword, etc. |

| tsuka | 柄 | handle; handgrip hilt |

| tsuka gashira | 柄頭 | the head of the hilt |

| tsume saki | 詰め先 | the lower tips |

| yoku | 翼 | wings |

Nunchaku

ヌンチャク

A nunchaku is a pair of linked sticks used as a flailing weapon. The two sticks of the nunchaku were once connected by cords of braided horsehair or human hair, strong enough to stop the slice of a sword. Most nunchaku movements are large flailing arcs. Nunchaku can also add extra reach to a thrust or punishing solidity to a punch or back-fist.

Origin

Nunchaku came from China. They are believed to have developed from a flail for soybeans – or possibly a type of horse halter. Some sources say a rice flail, but rice kernels are too fragile and would be crushed to powder.

Nunchaku Hojo-undō

There are four groups of nunchaku hojo-undō defined by Soke Kaichō Kinjō. Of course, you can always create your own hojo-undō for repetition of techniques that may be giving you problems.

Nunchaku Bunkai

Because of danger to the partner, there is no bunkai for Kōbu no Nunchaku. A few bunkai combinations can be performed safely – some by gripping both halves of the nunchaku in one hand and swinging as though they were free.

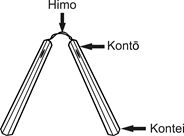

The Parts of a Nunchaku

| Himo | 紐 | string; cord |

| Kontei | 棍底 | base of a stick |

| Kontō | 棍頭 | head of a stick |

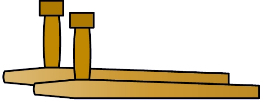

Tonkua

トンクヮー

The tonkua can be used to extend the reach and effectiveness of a punch. Gripped by the handle, it can be used to block, protecting the forearm. When gripped by the long end, it can be used like a hammer or to hook and deflect a bō or sword attack. Many tonkua movements look like the flailing of a nunchaku, but the handle is firmly gripped at contact to deliver power without recoil.

Origin

A possible origin could have been a device very similar in appearance to a tonkua that was used to hang pots in ancient Okinawa. Some sources say that the tonkua may have been a handle for a grindstone, for which it seems poorly designed.

The movement style and maybe even the design of the tonkua may have originated from the kurumambō (車棒), a type of grain flail for soybeans or wheat. The kurumambō is about six feet in length with a long arm that was gripped and a short arm connected by a peg that pivoted and struck the grain. Ancient kurumambō can be seen in a museum in Okinawa. There is a very similar wheat threshing tool used by the Amish. The kurumambō is one of the weapons of Matayoshi kobudō.

The tonkua in its extended orientation is also used in a shovel-like motion similar to that of another ancient tool called the tibiku (手鉾), an Okinawan potato spade. There is a modern version of the tibiku called the hera that is used as a spade.

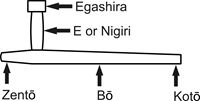

The Parts of a Tonkua

| Bō | 棒 | pole; rod; stick |

| Tsuka Hei E(eh) | 柄 | handle |

| Nigiri | 握り | grip |

| Heigashira | 柄頭 | head or top of the handle |

| Kōtō | 後頭 | back head |

| Zentō | 前頭 | front head |

Tinaka

手中

It has three pointed tips, each of which can be used to enhance the effectiveness of a punch or block.

Origin

Tinaka-like weapons were concealed in a warrior’s robe or hands or even in the hair. Tinaka were developed by Soke Kaichō Kinjō as a small weapon that could be easily carried and concealed.

The Parts of a Tinaka

| Nigiri | 握り【にぎり】 | grip |

| Saki | 先【さき】 | tip; end |

Ieku

イエーク

The ieku is a fisherman’s oar. An oar could be carried in public without it appearing to be a weapon. Like the bō, the ieku is used to strike, thrust, parry, sweep and smash. Since the edge of the paddle was often dented and dinged and rough with barnacles, it had a crude serrated edge. Therefore, strikes with the ieku are done with a slicing motion. The ieku could also be used to throw sand into an opponent’s eyes.

The ieku is unbalanced, having more weight on the paddle end. This enables the user to swing and strike with more force than a bō. However, the weight imbalance can be difficult to master, making the ieku an advanced weapon.

Origin

The ieku was an oar used by ocean-going craft typically manned by only one person. You can find antique oars in a museum in Okinawa that look just like the ieku that are sold by Shureido today. Motorboats in Okinawa still carry an ieku in case of emergency.

Apparently, the using an oar as a weapon is unique to Okinawa.

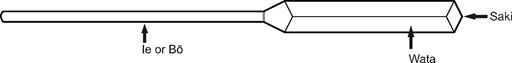

The Parts of the Ieku

The ekku is comprised of five main parts, they are as follows:

1. ushiro tsukagashira – the butt end of the oar.

2. saki – the tip of the oar blade.

3. moto – the center of the oar.

4. yoko – the side of the oar blade.

5. monouchi – the blade

| Bō | 棒 | pole; rod; stick |

| Saki Kissaki | 先 切っ先 | tip point of a sword, etc. |

| Tsuka | 柄 | handle handgrip |

| Mine | 峰 | peak; ridge |

| Wata | ||

| Ha | 刃 | the blade |

| Kontei | 棍底 | the base of a stick |

Or the ha – the edge of the blade

the mine – the spine or ridge

kissaki – tip or point of a sword, etc

tsuka – handle

kontei – the bottom

Nunti

ヌンティー

The most effective end, the manji sai end, of the nunti is used for hooking, pulling and piercing. Less effectively, the opposite end can be used like a bō.

Origin

While it looks something like a fisherman’s gaff, the nunti did not originate from the fishermen of Okinawa. The nunti was introduced into Okinawa from China about 600 years ago. In China, it was used from horseback to pull riders off of their horses. Matayoshi Shinko practiced with nunti on horseback during his time in China with the bazoku (horse tribe).

Kama

鎌

Origin

The kama was widely used throughout Asia to cut crops, rice in particular. Still used as a tool, kama are available for purchase in the hardware stores of Japan. In addition to slicing, the back of the blade, the kamachi, can be used to breaking up clods of dirt or even some friable types of rock.

Kama are especially common in the martial arts of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. in Okinawa’s ancient past as the seafaring country of Ryūkyū, Okinawans would have traded with these countries. This is thought to be the origin of the use of kama as a tool and a weapon in ancient Okinawa.

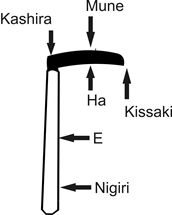

The Parts of a Kama

| Mune | 棟 | ridge of a blade |

| Ha | 刃 | edge of a blade |

| Tsuka Hei E(eh) | 柄 | handle |

| Kashira Kamachi | 頭 鎌頭 | head |

| Kissaki | 鋩 | point of a blade |

| Nigiri | 握り | grip |